The economic impacts of the pandemic, inflation, and market instability on young Black men

‘Prior to the pandemic — when the US labor market was in good health — the unemployment rate for black Americans was roughly twice that of white and Asian adults. In 2019, it stood at 6.1 per cent, compared to just 3.3 per cent and 2.7 per cent for white and Asian adults, respectively. [...] At the worst of the Covid economic crisis, the black unemployment rate skyrocketed to nearly 17 per cent. For white workers, it was slightly lower, at 14 per cent.’

Colby Smith ‘Black America’s record employment gains at risk as Fed tightens rates’ - Financial Times

To understand where young Black men find themselves economically at the start of 2023 we need to understand the inequalities of their position prior to 2020, as well as the disproportionate negative impacts they bore as a result of COVID-19, inflation, and the market instability being generated by the looming fears of recession.

As the headline quote demonstrates, prior to 2020 Black Americans faced structural inequalities that led to unemployment rates that were nearly twice that of their fellow White and Asian Americans. Such inequalities were only exacerbated by the economic repercussions of lockdowns and other measures implemented to reduce the spread of COVID-19. For example, between February 2020 and May 2020, the racial gap in employment between White and Black men increased by 43.7 percent. As the White House noted: ‘(t)he early months of the pandemic hit every American hard, but particularly Black Americans’ as unemployment rates came ‘higher and later’.

And it was Black men, in particular, who experienced ‘the highest unemployment rates of any race/gender group, and the lowest labor force participation and employment rates among men’ across that 2020-21 period. These results, as the Brookings Institute noted, are only made more ‘disturbing’ when you factor in that there is significant undercounting of Black men within this official data. Such an undercount only masks what was likely a much worse picture.

The disproportionate economic impact of COVID-19 on Black men was partly explained by the fact they found themselves in the type of low-wage jobs that were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, and partly explained by the fact that they also found themselves within industries that did not see the economic revival other sectors experienced by 2021. While high-wage jobs came back to pre-pandemic levels much faster, by early 2021 low-wage industries still remained down by 28%. And although the gap of rates of joblessness between Black and White Americans narrowed in the initial months of 2020, White Americans saw a much faster return to the workforce as a result of discriminatory hiring practices. As William Spriggs, chief economist of the AFL-CIO and Professor at Howard University, noted: “This is not a matter of skills [...] It’s a matter of the way discrimination takes place within recovery.”

Even the emergency extensions of benefits under the CARES Act of 2020 - that expanded the unemployment assistance to include part-time workers, independent contractors, and gig workers for the first-time - had a limited and disproportionate impact for Black workers. From April to June 2020 only 13% of jobless Black workers received these emergency benefits compared to 24% of jobless White workers. For many White households access to both these emergency benefits and accumulated wealth helped stabilize their financial situation until the next job was secured. Whereas for Black families, especially where low-wage working Black men were the breadwinners of the household, limited access to both these emergency benefits and accumulated wealth left them in a much more vulnerable position as lockdowns and other restrictions began to be eased.

The precariousness of this situation for Black workers was only compounded by the effects of the racial wage gap with Black men, on average, earning $0.87 for every $1 their White male counterparts earned. Dispiritingly, this wage gap only widens as Black men move up the corporate ladder. So while the disparity between Black and White Americans in educational attainment has narrowed the wage gap has not, with ‘Black workers mak[ing] about 80 percent of the earnings of a white worker with similar education’. Furthermore, Black workers with college degrees are still facing higher levels of unemployment compared to people from other races who had obtained less than a high school education. All this points to the fact that while the equalization of educational attainment and opportunity for Black men should be celebrated, it does not automatically translate to the equalization of economic attainment and career progression.

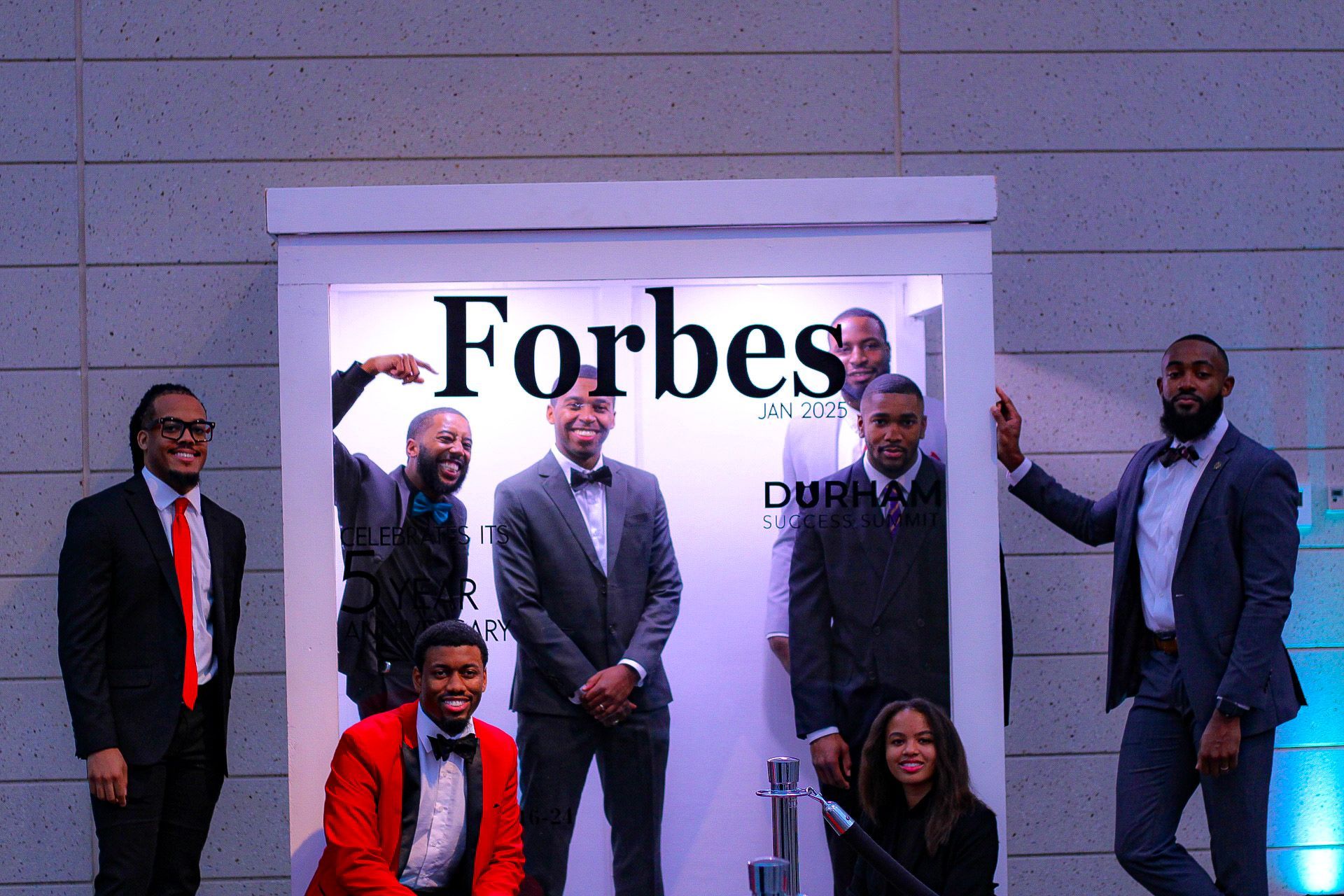

It is why we here at DSS know how important it is that young Black men are exposed to various career path opportunities, valuable work experience, and the chance to build a robust employment history through our Scholars program.

Looking towards 2023 amidst the specter of recession

Yet, as we moved through 2022 and into 2023 there were some green shoots of hope and recovery for Black Americans. As labor shortages continue, even in the face of increased layoffs and the threat of recession, the gap between the employment of Black and White Americans of “prime working age” (25-54 years old) has narrowed to new record lows. There were also signs of progress in terms of employment for Black men, specifically, across 2022 with the unemployment rate decreasing from 7.1% in January to 5.1% by December, although this compares with an end of year rate of 2.7% for White men. Moreover, the White House, in its August 2022 report on the pandemic labor market, noted that Black workers were seeing both a ‘modest’ positive median real wage growth (one factoring in the effects of inflation) and a move into more traditionally high-wage industries. What the Biden administration trumpeted as ‘signs of genuine progress’.

Six months on from that report, however, these gains are under the double threat of further inflation and the Federal Reserve’s multiple interest rate hikes that threaten to undermine one of the hottest labor markets that has effectively driven this progress. The early signs of these impacts have already begun to show within the tech industry where layoffs that began in the early fall are showing no signs of slowing down with a further 50,000 job losses in January 2023. And these layoffs are disproportionately impacting Black and Brown workers in an industry ‘which offers some of the best paid jobs’ and that can and should be doing more to bridge the Black talent gap.

As talk of recession starts to dominate the economic conversation, Black Americans face this in the knowledge that they ‘have historically suffered, when compared to mainstream America, during any economic downturn.’ Yet, despite this, a recent survey by JPMorgan Chase has shown ‘Black small business owners are more confident than their peers about how they will execute overall in 2023.’ This is a bullishness characterized by the young Black men in our Founders program as they progress through their intensive 6-month business incubator with the support of secured seed funding to help make their entrepreneurial aspirations a reality.

Our Founders, however, do this within a wider context in which Black entrepreneurs receive less than 2% of overall VC funding. In fact, 2022 saw a 45% decrease in VC financing for Black entrepreneurs against an overall average 36% decrease. Such decreases effectively reversed historic year-over-year gains for Black founders in the wake of the George Floyd racial justice reckoning in 2021. On this point, we encourage private investors to take note of a recent McKinsey & Company report on how they can more effectively support Black-owned businesses and help invest in wider Black economic mobility.

In the wake of COVID-19, we also note that another key component to creating sustained mobility for Black Americans, and the young Black men we work with here at DSS, is to tackle the inequalities they face in accessing an economy that has undergone a digital transformation. These barriers come in the form of infrastructure - with 40% of Black American households (compared to 28% of White American households) not being able to access high-speed, fixed broadband. They also come in the form of being able to access digital skills training - with a 2020 OECD survey finding that roughly half of Black workers (compared to 77% of White workers) had ‘the advanced or proficient digital skills needed to thrive in our increasingly tech-driven economy’.

The last few years have revealed that the structural inequalities that the young Black men we work with here at DSS face have only been complicated and exacerbated by the disproportionate economic impacts of the pandemic, of inflation, and of increasing market instability. It is important that we take stock of these lessons at the start of 2023 as our Scholars and Founders face their futures with determination